第6章 GETTING THE MEMO

On April 7, 2016, I did what I thought would be a fairly routine radio interview with commentator and friend Roland Martin. The topic was turning our inner city and our underserved communities around, and I assumed it would be a straightforward discussion. No drama here, I thought.

I was dead wrong.

During the course of the interview, I mentioned something I wrongly assumed everyone already knew: Slavery was first and foremost economic in nature. It was about money and wealth before it was about anything else. It was about free labor.

The radio station switchboard lit up.

I went on to explain that slavery—as immoral and cruel as it obviously was—was primarily and at its core about building a country for free, and building wealth for some (i.e., Southern plantation owners) through what I call “bad capitalism.”

The message board on the Roland Martin Show was going crazy, and not in a good way. But I hadn't a clue; I just kept on talking.

To me, this was plain common sense. It was not an emotional issue for me. It was simply a stack of statistical facts for us all to understand and a problem for us to then solve: how do we go forward?

It wasn't that I didn't feel the injustice. I did and I do. My great-great-grandfather on my father's side was born on a Southern plantation in the Deep South. Mississippi, to be exact.

My grandmother on my mother's side gave birth to her children in a shotgun shack in Alabama, later moving the entire family to the relative luxury of East St. Louis (for those who don't know East St. Louis, “relative luxury” is a joke).

Yes, I do understand the injustice. I do feel the pain.

But I also know that my feelings and my emotions about it do nothing to help right this wrong or to help move us forward from the effects of that period, many of which linger on even to this day.

I knew that I would need my brain for that task. I needed to be clearheaded and nonemotional, too. I needed to work from the neck up.

My listening audience on this day saw things through a completely different lens, though. They were pissed. At me.

I went on to explain during the course of the interview that in 2016, we still have a version of what I call modern slavery in our own urban, inner-city neighborhoods, and this so-called enslavement is all economic.

In these places, fully 99 percent of all our most pressing challenges and daily stresses—from joblessness to crime and violent crime, to high homicide rates, to high school dropout rates, to massive levels of the most basic illiteracy, crushed family structures, and an overwhelming lack of homeownership and business ownership—were focused in 500-credit-score neighborhoods.

You can literally take a 500-credit-score map and overlay it on top of all the worst problems plaguing all the communities in which people in our Invisible Class reside—urban, suburban, and rural. They match up perfectly.

But for me it's not really about the credit score; it's about identifying powerful and yet unseen trend lines and intersection points that are or could be transformational for communities. Credit scores are leading indicators, trend lines for the kind of energy present in a neighborhood.

To me, credit scores—very much unlike racism or bias or discrimination and countless other things that bedevil the Invisible Class (and the African American race of people specifically) on a daily basis—are fantastic because they are so measureable.

They are just one powerful example of a nonemotional scientific indicator of success that lets you feel good about the progress you are making. You can see how the changes you are making move your score up the chart—and believe me, a 100-point increase in your credit score signals an improvement in your life around much more than just your score! It signals more options, more freedom, more hope.

But while I was busy being rational and nonemotional on the topic, large portions of the listening audience were going stark raving mad, lashing out at me wherever they could track me down on social media.

I discovered this mini-crisis of confidence (in me) within my own community on my way to the airport in Washington, DC. It was bad, and it was constant. I simply couldn't keep up with the barrage of criticism, complete with folks calling me an Uncle Tom and a coon, in a continual stream of interchangeable phrases. I was being bullied and overwhelmed on social media, mostly on my Twitter account.

Luckily, I was able to set this critiquing of me aside and to think clearly—once again from the neck up—about what was really going on here and what was really important. And I quickly found that 140 characters on Twitter was simply insufficient to communicate what I really meant.

What We Don't Know That We Don't Know

I remember having some powerful thoughts about what I was hearing and experiencing from my people on that day:

1. We are emotional in response to our problems.

2. We are frustrated in relation to our lack of being seen or heard.

3. We are all too often simply “angry for a living.”

4. Worst of all, we are becoming cynical as a new and constant norm.

I remembered that powerful Malcolm X quote in which he laments, “You've been took. You've been hoodwinked. Bamboozled….”

It is precisely what I thought was happening at the time. But this time, it was us tricking ourselves.

We could not hear, yet alone analyze, a clearheaded and wide-eyed presentation of the facts because our emotions had taken over. And when that happens, the racist that everyone despises and says they are rallying against actually wins. When our emotions distract us from the real truths, then our hope dies. And the one thing I know for sure from my twenty-five years with Operation HOPE is that the most dangerous person in the world is a person with no hope.

I decided that I had to do something.

I believed that there were a whole set of facts, realities—even opportunities—that we were missing altogether, because we were so utterly focused on our pain. We felt that this pain made us invisible, unheard, and unimportant, and we were determined to have our pain noticed.

Understandable? Yes. But productive? No.

I believe that membership in the Invisible Class today—and certainly our ability to leave the Invisible Class tomorrow—has less to do with our history and more to do with our credit scores (and what we do to raise them).

I believe that getting the Memo triggers very real and sustainable resolutions to a vast majority of problems plaguing my community and other communities of poor, struggling, and powerless people the world over (i.e., the Invisible Class)—including my poor white brothers and sisters right here in rural America.

I wanted to share that message with my dissenters. But first I needed to regain the higher ground—and get a little personal dignity back, too.

I could not be a punk and simply retreat behind the safe walls of my comfortable home and my curated private life.

I could not simply return to my successful business because I did not like the response that my people offered me.

I needed to step up, because while I was convinced that my people were utterly brilliant, in this case, it was what we didn't know that we didn't know (but that we thought we knew!) that was killing us. And so, I responded, writ large.

I took to a tool I had just discovered (also through Roland Martin) called Facebook Live.

I recorded a short eight-minute video en route to the airport entitled “Modern Slavery,” and I did it live so I could not punk out later and not publish.

I recorded a passionate and powerful message, stepped out of the car and right into the airport terminal, preparing myself for the avalanche of what I assumed would be even more ramped-up criticisms.

The central message of the video was this:

While we are busy being angry, exhausting ourselves chasing a racism and bias ghost that is akin to the boogeyman of our childhood, in urban, inner-city, and rural underserved neighborhoods something else very real and tangible is happening—and you can actually see and do something about it!

In each and every one of those communities, here is what you see: a check casher, next to a payday loan lender, next to a rent-to-own-store, next to a renting rims store (yes, I mean twenty-inch rims for your car with spinners attached), next to a liquor store.

What does this mean? It means a one-trillion-dollar junk credit industry is not only preying on you, they are effectively robbing you and those you love in plain sight. In broad daylight.

And they are not even preying on black communities per se. They are targeting the 500-credit-score customer, regardless of race. Literally targeting them. I promise you'll see every color of the rainbow in the faces of people standing in line for a payday loan.

If you live in rural poor white America, you see the same check-cashing stores, the same crumbling store-fronts, the same low-quality food options as you do in poor urban neighborhoods. If you live on a military base, which includes all races of people, you will see much the same, plus other businesses that signal despair and depression.

Heck, given our low level of financial literacy and understanding of money and the market economy, you are now beginning to see these same things in working middle-class neighborhoods that also never got the Memo.

And so today these groups feel just as ignored and invisible as the black youth in our inner cities. Everyone wants to feel seen.

My point was that the base of all our problems is economic in nature. But all too often, far too many of us see the economic status quo as normal.

It is not normal.

And the result of my bold retort? More than three million video views, eleven thousand comments, and twenty thousand shares on this short eight-minute video—and 95 percent of the comments were positive, supportive, and affirming.

Even better, it was the overwhelmingly African American audience of commenters that began the pushback against the coon and Uncle Tom criticisms directed at me. They explained to the others not only what I really meant but also how they were 100 percent with it—and with me.

So, What Are We Going to Do About It?

The majority of commenters who responded positively to my video understood that racism is like rain: It's either falling someplace or it's gathering someplace else. You might as well get out an umbrella and start strolling through it—it's not going to change, and so we must.

It was then that I knew we had a chance for a new movement, a movement to liberate the Invisible Class from predators and indifference, to change (i.e., empower) ourselves because we cannot always change the ignorance and backwardness of others around us.

Essentially, the Memo says this: I know and recognize that we are dealing with serious problems of inequality and unfairness. AND NOW WHAT? What are we going to do about it?

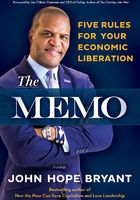

What we do is we change our narrative by living well. That is what this book is about. The Memo gives you five simple rules for moving forward to economic independence. I promise these rules apply to you wherever you are, whoever you are.

Let's go.